|

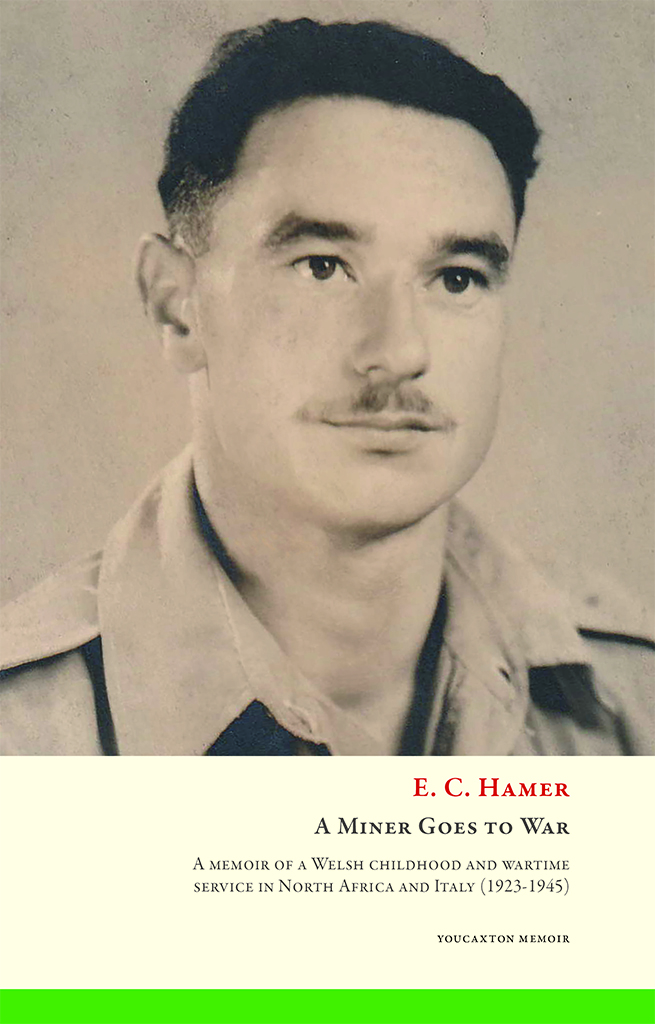

A memoir of a Welsh childhood and wartime service in North Africa and Italy (1923-1945) Edited by Pat Wilson, Ernest Hamer and Anne Kleiser Eddie Hamer’s memoir gives a unique insight into working-class life in the first half of the 20th century. It is often humorous, sometimes angry, and always informative. It begins with a history of his workingclass Welsh mining family, based on his own memories and on a series of discussions with his father in the 1960s - while there was still time to record first-hand accounts of his family’s story in the decades before he was born. There follows his childhood in Huddersfi eld and North Wales in the 1920s. The poverty and hardship that his family endured is vividly described and the now-unthinkable responsibilities he had to shoulder at a young age - but this was also a boyhood of freedom, camaraderie and adventures. The final sections of Eddie’s memoir are based on the diaries he kept during his service in World War 2: his training in the U.K. and his service in North Africa and Italy as a gunner in the Royal Artillery. |

£11.99 (+ £3.00 postage) |

||||||||

|

After the war he qualified and eventually became Chief Mining Surveyor in two collieries in South Wales. He was married with one son and one daughter and died in 1990. |

||||||||||

Alison Hembrow, The Royal Regiment of Wales Museum

This book is a gem: a combination of recollections of working-class childhood and early adulthood in the first half of the twentieth century, family stories, and war diaries – all seen through the lens of a fiercely independent man with strong socialist views. It’s a valuable first-hand insight into lives and times that are in danger of being forgotten. It’s also a gripping and eye-opening read which has been carefully brought to press by members of Eddie Hamer's family who recognise the importance of his memoir.

“A Miner Goes to War” is presented in two distinct halves. The first is recollections of childhood and early life growing up in a working-class family in Wales and Yorkshire in the 1920s and 1930s. Recorded several decades later, Eddie's strong left-wing views shine through in his emotive descriptions of his family being part of “the rabble of history”. His mother’s family were Welsh miners, his father's family woollen workers from mid-Wales, both struggling to find regular employment and make ends meet.

Moving to Yorkshire in search of work, Eddie’s family found themselves in cramped accommodation unfit for human habitation. His early teens featured trips to the abattoir to collect a bucket of intestines to provide meals, war-wounded teachers, earth closets, early deaths, and further deprivation during the General Strike.

At 14 Eddie leaves school and goes down the mine. He and his family are now in north Wales. Detailed descriptions of the working conditions, equipment used, and jobs done give an insight into a harsh world in which pit disasters and deaths were frequent. His aptitude is spotted and he starts night school classes to qualify as a mining surveyor.

Although the memories aren’t all chronological, and they are seen through the prism of Eddie's adult beliefs, they give a strong flavour of lives which were lead by many but recorded by few. Interspersed with vignettes touching on current affairs, they bring to life an existence experienced by millions in a way a more traditional historical account cannot.

Photos and hand-drawn maps and plans divide this first section from Eddie's war diaries which form the second half of the book. These diaries have a different character altogether. Written as he completed his basic training as a gunner in the Royal Artillery and served in North Africa and Italy, they have an immediacy and level of detail that gives a sobering insight into the day-to-day experiences of a soldier and the horrors of war.

Eddie brings an admirable humanity to his encounters on active service: fetching a medical orderly to dress the wound of a young Italian girl, sharing water-melons with Arab children, cooking fried tomatoes with locals. His interests are wide-ranging: he describes the workings of Italian bombs, the quality of German dugouts, the architecture of mosques, the historical interest of Pompeii compared with the squalor of Naples, and rearing Regimental turkeys for Christmas lunch. He also records the 104 degree fever he suffered, the horrors of rampant dysentery in the regiment, the limbs lost by close comrades in a premature explosion, and cemeteries full of teenage German casualties.

When Eddie's narrative ends in 1944 , his brief notes and Release Leave Certificate are included as an Afterword. His military conduct was officially described as “Exemplary”. “A Miner Goes to War” is exemplary in preserving for future generations and researchers the personal experience of an upbringing in a mining family and service in World War Two. Having just read Captain Tom Moore’s “Tomorrow Will Be A Good Day”, I can see parallels in two accounts of growing up in the 1920s and serving in World War Two from contemporaries who both bring a personal perspective to aspects of national history.

Books such as this add a different dimension to more traditional accounts, and are a valuable addition to the bookshelves of anyone wanting to find out more about aspects of life in the first half of the 20th century.

Review of “A Miner Goes to War” by Neil Wilson

I really enjoyed “A Miner Goes to War”. The memories are personal, but they seem to capture the period very well. It’s a powerful reminder of what the world was like when the welfare state was a lot smaller. Anyone who utters the words, ‘safety gone mad’, will be reminded of what the world could be like; a world where people get killed in accidents and everyone else carries on working. Reading this book made me realise how much we take for granted in modern Britain. Social improvements were hard won, and can be easily lost.

It’s a book with powerful contrasts. This was an era when kids could play on the local scrap heap, build tree houses in the woods, swim in the river and crawl under the market stalls looking for fruit. But this childhood freedom is tinged with a sense of fatalistic sadness. Once he was in the army, he never knew where he would be in a few hours. Every moment of the day was planned for him, mingled with the unexpected attack from a passing plane or an ambush.

Each memory is filled with powerful emotions, taking the reader back in time. As he walks through the woods past a house that’s supposed to be haunted, we imagine how we’d have felt as young child. There are moments of tension, when a farmer catches them stealing apples. Moments of enchantment, when his uncle dresses up as Father Christmas. Moments of anger, when workers are deliberately under paid. We see the world through E. C. Hamer’s eyes, and grow older with him. He really captures how a person thinks at different ages, but with little retrospectives showing how he saw things as an older adult. Considering how much hardship there is, from the miners’ strike to the war, there’s a positive feeling to the book. There are many moments of camaraderie, from the kids building a bonfire together, to the miners playing their instruments underground. There’s a feeling that people do come together in the face of adversity.

E. C. Hamer captures the realities of war very well. There are so many details, like the friendly fire, the shells that malfunction, trading soap for eggs with the locals, the ‘enemy’ leaving dirty protests in the houses before they retreat and the German deserters they find hiding in a cave.

His account comes across as remarkably honest. E.C Hamer has a lot to be proud of, but he also shares his regrets, including one time as a child when he was peer pressured into putting a firework through someone’s letter box. It’s a combination of stark honesty, bravery, hard work, empathy, ironic humour and self reflection, that makes E.C. Hamer such a likeable narrator.